Introduction

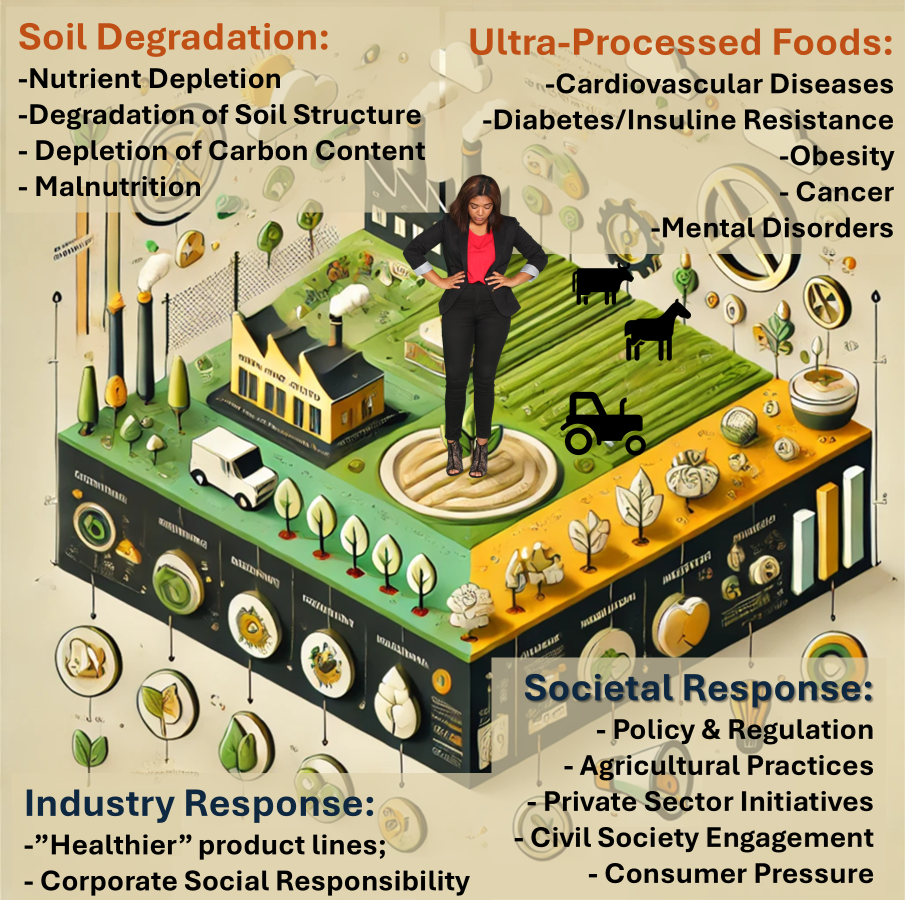

The global food industry, dominated by ultra-processed foods (UPFs), is increasingly recognized as a significant threat to public health. These foods are linked to a variety of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer (Fiolet et al., 2018; Srour et al., 2019). Another critical, yet often overlooked dimension of this problem is the declining quality of agricultural products due to poor soils. Modern agricultural practices, which prioritize the use of synthetic fertilizers rich in nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), neglect other essential nutrients. Also the structure & content of the soil carbon has been degraded. This exacerbates further the nutritional deficiencies of both raw and processed foods, compounding the global health crisis (Lal, 2009; Davis et al., 2004).

The Proliferation and Health Impacts of Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods have become a dominant feature of diets worldwide. These foods, characterized by their high content of sugars, unhealthy fats, and sodium, coupled with a lack of essential nutrients, are produced through extensive industrial processes. The convenience and palatability of these foods have made them popular, but their overconsumption is closely linked to a surge in obesity, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer (Monteiro et al., 2019; Fiolet et al., 2018).

Moreover, ultra-processed foods (UPFs), rich in sugar, unhealthy fats, and additives, are designed to be hyper-palatable, triggering addictive responses similar to those seen with drugs by activating the brain’s reward system, particularly through the release of dopamine (Schulte et al., 2015). This addiction is particularly concerning in children, whose developing brains are more susceptible to forming strong food preferences and habits that can persist into adulthood (Gearhardt et al., 2011). The habitual consumption of UPFs, reinforced by aggressive marketing, especially to children, leads to a cycle of cravings and overconsumption, contributing to obesity and related health issues (Ziauddeen, & Fletcher, 2013). This addiction increases the risk of chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and mental health disorders (Fiolet et al., 2018). Addressing UPF addiction requires public health interventions that limit exposure, particularly among vulnerable populations like children.

1. Obesity and Metabolic Disorders

The consumption of ultra-processed foods is a major driver of the global obesity epidemic. The high-calorie, low-nutrient content of these foods leads to excessive caloric intake without providing the essential nutrients needed for health. According to Fiolet et al. (2018), higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is strongly associated with obesity and related metabolic disorders, a trend that is exacerbated by the declining nutrient density of agricultural products (Davis et al., 2004).

2. Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular diseases are another significant concern associated with ultra-processed foods. These foods are typically high in trans fats, sodium, and sugars, all of which contribute to heart disease and stroke. Research by Srour et al. (2019) indicates that diets high in ultra-processed foods are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular events. This risk is further compounded by the low levels of heart-protective nutrients, such as magnesium, found in crops grown in nutrient-depleted soils (Rengel & Graham, 1995; White & Broadley, 2005).

3. Diabetes and Insulin Resistance

The high glycemic load of ultra-processed foods, coupled with low nutrient density, contributes to the growing prevalence of type 2 diabetes. As detailed in a study by Mendonça et al. (2017), diets rich in ultra-processed foods are associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The poor nutritional quality of these foods, derived from crops grown in depleted soils, further aggravates this condition, as the body struggles to manage blood sugar levels without adequate micronutrient support (Zhao et al., 2007).

4. Cancer Risk

Emerging evidence links the consumption of ultra-processed foods to an increased risk of cancer. A study by Fiolet et al. (2018) found that higher intake of ultra-processed foods correlates with a higher risk of overall cancer and breast cancer. The presence of carcinogenic compounds formed during food processing, along with the low levels of protective nutrients in the base ingredients due to poor soil quality, may contribute to this elevated risk (Beach RH, et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2008).

5. Risk of mental disorders

A Harvard study, assessed the impact of dietary habits on mental health. People who consumed the most processed foods – which include items such as sodas, chips, cookies, white bread and ready-to-eat meals – at nine or more servings a day were 50% more likely to develop depression than those who consumed no more than four servings a day. Consumption of many foods and drinks containing artificial sweeteners was associated with a particularly large increase in the risk of depression. The study was observational, meaning that it could not absolutely prove that processed foods cause depression, only that there was an association. Ultra-processed foods can disrupt the proper balance of gut bacteria, which affects how the brain works, the study authors said. Artificial sweeteners can interfere with chemicals in the brain that help nerve cells communicate normally (Samuthpongtorn C, et al.,2023).

The Impact of Soil Degradation on Food Quality and Health

Modern agricultural practices have contributed significantly to the decline in soil health. The focus on maximizing crop yields through the application of NPK fertilizers has led to the neglect of other vital micronutrients such as magnesium, zinc, iron, and selenium, which are crucial for human health (Gupta & Gupta, 2000; Cakmak & Marschner, 1988). Over time, soils become depleted of these nutrients, leading to crops that are less nutritious. Moreover, deterioration of carbon content and structure in soils causes the lover water retention and decreases yield. This soil depletion is not only a concern for raw agricultural products but also for the ultra-processed foods derived from them, further deteriorating the nutritional quality of the global food supply (Davis et al., 2004; Mayer, 1997).

1. Nutrient Depletion and Food Quality

Studies have shown that the nutritional content of crops has been declining over the past several decades. For instance, a comprehensive study by Davis et al. (2004) found significant reductions in the levels of essential nutrients in fruits and vegetables since the 1950s. This decline is attributed to soil depletion caused by modern agricultural practices focused on high yields rather than nutritional quality (Fan et al., 2008). The resulting crops, which are used as raw materials for processed foods, are inherently less nutritious, compounding the health risks associated with UPFs (Welch & Graham, 2004).

2. Degradation of Soil Structure and Carbon Content

The degradation of soil structure and carbon content is a critical issue that exacerbates the declining quality of agricultural products and, consequently, global health. Healthy soil structure is essential for maintaining water retention, nutrient availability, and root growth. However, intensive agricultural practices, such as over-tilling, monocropping, and excessive use of chemical fertilizers, have led to the breakdown of soil aggregates, resulting in soil compaction and erosion (Lal, 2004).

Moreover, these practices deplete the organic carbon content in the soil, which is crucial for soil fertility and microbial activity. Soil organic carbon acts as a key component of soil health, influencing nutrient cycling and the soil’s ability to sequester carbon dioxide, thereby mitigating climate change. The loss of soil carbon not only diminishes the soil’s capacity to support healthy crop production but also contributes to higher atmospheric carbon levels, intensifying the global climate crisis (Smith et al., 2015; Lal, 2004).

Addressing soil structure degradation and carbon loss requires adopting sustainable farming practices, such as reduced tillage, cover cropping, and organic amendments, to restore soil health, increase soil water retention, improve crop quality, and enhance global food security (Lal, 2015).

3. Impact on Public Health – Malnutrition

The combination of poor soil health and the proliferation of ultra-processed foods creates a “double burden” on global health. Populations are not only consuming foods that are high in unhealthy components but also low in essential nutrients due to soil degradation (Smith et al., 2016). This scenario exacerbates micronutrient deficiencies, leading to increased susceptibility to chronic diseases. For example, the lack of zinc in soils, and consequently in crops, has been linked to higher rates of immune deficiency and infectious diseases, as detailed by Brown & Wuehler (2000) and discussed in The Lancet (Swaminathan, 2003).

Global Health Implications and Industry Response

The global health implications of the widespread consumption of ultra-processed foods, compounded by declining soil health, are severe. The rise in non-communicable diseases, driven by these factors, presents a major challenge to public health systems, particularly in developing countries where both undernutrition and overnutrition are prevalent (Barrett, 2010; Cordell et al., 2009).

The food industry’s response to these challenges has been largely superficial, focusing on the introduction of “healthier” product lines without addressing the underlying issues of soil degradation and nutrient depletion (Glanz & Yaroch, 2004). While some companies are beginning to explore more nutrient-dense food options, the scale of the problem requires a more fundamental shift in both agricultural practices (including innovative organic fertilizers) and food processing methods (van der Wiel et al., 2023).

Societal Response to Global Health Implications

The global health implications of widespread consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and the degradation of soil health present a multifaceted challenge that requires coordinated action from governments, the private sector, civil society, and individuals. The societal response must address both the immediate health impacts and the underlying environmental and economic drivers that exacerbate these issues.

1. Policy and Regulation

Governments play a crucial role in shaping the food environment and mitigating the negative health impacts associated with UPFs and soil degradation. Effective policy and regulatory measures can include:

- Nutritional Guidelines and Public Awareness: Governments can promote dietary guidelines that emphasize the consumption of whole foods and reduce reliance on ultra-processed products. Public health campaigns can raise awareness about the health risks of UPFs and the importance of nutrient-rich diets, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children and low-income groups (Monteiro et al., 2019; Fiolet et al., 2018).

- Taxation and Subsidies: Implementing taxes on unhealthy foods, such as sugary beverages and high-fat snacks, can discourage their consumption. Conversely, subsidies for fruits, vegetables, and other whole foods can make healthier options more accessible and affordable. For instance, Mexico’s sugar tax, introduced in 2014, has shown promising results in reducing the consumption of sugary drinks (Colchero et al., 2016).

- Food Labeling Requirements: Clear and informative food labeling can help consumers make healthier choices. Mandatory front-of-package labels that indicate high levels of sugar, fat, and sodium can deter the purchase of ultra-processed foods. Some countries, like Chile and Brazil, have already implemented such labeling systems with positive outcomes (Taillie et al., 2020).

- Regulation of Marketing Practices: To protect vulnerable groups, particularly children, stricter regulations on the marketing of ultra-processed foods are necessary. Limiting advertising during children’s programming and restricting the use of cartoon characters and celebrities in marketing unhealthy foods can reduce children’s exposure to these products (Sadeghirad et al., 2016).

2. Agricultural Practices and Soil Management

Improving agricultural practices is essential to address soil degradation and enhance the nutritional quality of food. This requires a shift towards sustainable farming practices that prioritize soil health and biodiversity:

- Sustainable Farming Techniques: Promoting techniques such as crop rotation, cover cropping, reduced tillage, and the use of organic fertilizers can help restore soil structure, increase soil organic carbon content, and improve water retention (Lal, 2004; Smith et al., 2015). These practices can enhance the resilience of agricultural systems to climate change and improve the nutritional content of crops (Bouis & Welch, 2010).

- Support for Small-Scale Farmers: Governments and NGOs can support small-scale farmers in adopting sustainable practices by providing access to resources, education, and financial incentives. These farmers often face barriers to implementing sustainable methods due to limited access to technology, knowledge, and capital (Altieri, 2009).

- Agroecology and Agroforestry: Integrating trees and other perennial plants into agricultural landscapes (agroforestry) can improve soil health, sequester carbon, and increase biodiversity. Agroecology, which emphasizes the ecological management of farming systems, can also play a critical role in creating more resilient and sustainable food systems (Gliessman, 2015).

3. Private Sector Initiatives

The private sector, particularly food manufacturers and retailers, has a significant influence on the food environment and consumer choices. Companies can contribute to the societal response by:

- Reformulating Products: Food companies can reduce the levels of sugar, fat, and salt in their products and remove harmful additives. Reformulating UPFs to make them healthier while maintaining taste and affordability can help reduce the public health burden associated with these products (Mozaffarian et al., 2018).

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Companies can engage in CSR initiatives that support sustainable agriculture, improve food security, and promote healthy eating. For example, investing in sustainable sourcing of ingredients or supporting educational programs about nutrition can enhance a company’s reputation while contributing to public health (Hartmann et al., 2015).

- Innovating Healthier Products: The development of new, healthier food products that cater to the growing consumer demand for nutritious and convenient options can drive industry change. This includes increasing the availability of minimally processed foods and creating alternatives to highly processed snacks and meals (Pereira-Kotze C, et al., 2022).

4. Community and Civil Society Engagement

Civil society organizations, community groups, and NGOs play a crucial role in advocating for healthier food environments and supporting grassroots initiatives that promote sustainable agriculture and healthy eating:

- Community-Led Initiatives: Local initiatives such as community gardens, farmers’ markets, and food cooperatives can improve access to fresh, local, and nutritious foods. These initiatives also strengthen community ties and empower individuals to take control of their food choices (Wakefield et al., 2007).

- Educational Programs: NGOs and community organizations can provide education on nutrition, sustainable agriculture, and cooking skills, particularly in underserved communities. These programs can help people understand the importance of healthy eating and how to prepare nutritious meals on a budget (Drewnowski et al., 2010).

- Advocacy for Policy Change: Civil society organizations can advocate for stronger government action on food policy and environmental protection. By mobilizing public support and engaging in policy dialogue, these organizations can influence decision-making and drive systemic change (Lang & Rayner, 2012).

5. Individual Actions and Consumer Choices

Ultimately, individual choices play a significant role in shaping the demand for ultra-processed foods and the sustainability of agricultural practices. Consumers can contribute to societal change by:

- Making Informed Choices: Educating oneself about the health impacts of ultra-processed foods and the importance of soil health can lead to more informed purchasing decisions. Choosing whole, minimally processed foods and supporting sustainable agricultural products can drive demand for healthier options (Lal, 2009; Monteiro et al., 2019).

- Reducing Food Waste: Reducing food waste is another important individual action that can contribute to global sustainability. By planning meals, using leftovers, and composting organic waste, consumers can reduce the environmental impact of their food consumption (FAO, 2011).

- Supporting Sustainable Brands: Consumers can choose to support brands that prioritize sustainability, ethical sourcing, and healthy products. By directing purchasing power towards companies that align with these values, individuals can encourage the broader food industry to adopt more sustainable practices (Hartmann et al., 2015).

In Summary: Addressing the global health implications of ultra-processed food consumption and soil degradation requires a comprehensive societal response that involves coordinated action from governments, the private sector, civil society, and individuals. By implementing policies that promote healthy eating, sustainable agriculture, and consumer education, society can mitigate the health and environmental impacts of these challenges and move towards a more sustainable and equitable food system.

Conclusions

The convergence of soil degradation and the proliferation of ultra-processed foods represents a significant threat to global health. The depletion of essential nutrients in soils, coupled with the rise of nutrient-poor processed foods, exacerbates the global burden of non-communicable diseases. Addressing this issue requires a multi-faceted approach, including:

- adoption of sustainable innovative agricultural practices (including organic fertilization),

- stricter regulation of food processing and innovative agricultural practicies,

- incentives for less processed food,

- greater public awareness of the nutritional quality of foods.

This publication has been inspired by the interesting article in The Economist (Aug 18, 2024), section business: Can big food adapt to healthier diets? https://www.economist.com/business/2024/08/18/can-big-food-adapt-to-healthier-diets#

References

- Altieri, M. A. (2009). Agroecology, small farms, and food sovereignty. Monthly Review, 61(3), 102-113.

https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-061-03-2009-07_8 - Barrett, C. B. (2010). Measuring food insecurity. Science, 327(5967), 825-828.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182768 - Beach RH, et al. (2019). Combining the effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on protein, iron, and zinc availability and projected climate change on global diets: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. Jul;3(7):e307-e317.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30094-4. - Bouis, H.E. and Welch, R.M. (2010), Biofortification—A Sustainable Agricultural Strategy for Reducing Micronutrient Malnutrition in the Global South. Crop Sci., 50: S-20-S-32.

https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2009.09.0531 - Brown, K. H., & Wuehler, S. E. (2000). Zinc and human health: results of recent trials and implications for program interventions and research. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 21(4), 440-443.

https://archive.unu.edu/unupress/food/fnb22-2.pdf - Cakmak, I., & Marschner, H. (1988). Zinc-dependent changes in ESR signals, NADPH oxidase and plasma membrane permeability in cotton roots. Physiologia Plantarum, 73(1), 182-186.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1988.tb09214.x - Colchero, M. A., et al. (2016). Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. BMJ, 352, h6704.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6704 - Cordell, D., Drangert, J. O., & White, S. (2009). The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought. Global Environmental Change, 19(2), 292-305.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.009 - Davis, D. R., et al. (2004). Changes in USDA Food Composition Data for 43 Garden Crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409 - Drewnowski, A., & Darmon, N. (2010). The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(1), 265S-273S.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.1.265S - Fan, M. S., et al. (2008). Evidence of decreasing mineral density in wheat grain over the last 160 years. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 22(4), 315-324.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2008.07.002 - FAO (2011). Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Rome.

https://www.fao.org/4/mb060e/mb060e00.pdf - Fiolet, T., et al. (2018). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. The BMJ, 360, k322.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k322 - Gearhardt, A. N., et al. (2011). Can food be addictive? Public health and policy implications. Addiction, 106(7), 1208-1212.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03301.x - Glanz, K., & Yaroch, A. L. (2004). Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: policy, pricing, and environmental change. Preventive Medicine, 39(Suppl 2), S75-S80.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.004 - Gliessman, S. R. (2015). Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1201/b17881 - Gupta, U. C., & Gupta, S. C. (2000). Selenium in soils and crops, its deficiencies in livestock and humans: Implications for management. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 31(11-14), 1791-1807.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00103620009370538 - Hartmann, M., & Siegrist, M. (2015). Consumer perception and behavior regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 44(1), 2-11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2016.12.006 - Lal, R. (2004). Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science, 304(5677), 1623-1627.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1097396 - Lal, R. (2009). Soil degradation as a reason for inadequate human nutrition. Food Security, 1(1), 45-57.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/S12571-009-0009-Z - Lal, R. (2015). Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation. Sustainability, 7(5), 5875-5895.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055875 - Lang, T., & Rayner, G. (2012). Ecological public health: the 21st century’s big idea? An essay by Tim Lang and Geof Rayner. BMJ, 345, e5466.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5466 - Mayer, A. M. (1997). Historical changes in the mineral content of fruits and vegetables. British Food Journal, 99(6), 207-211.

https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709710181540 - Mendonça, R. D., et al. (2017). Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN Project. American Journal of Hypertension, 30(4), 358-366.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpw137 - Monteiro, C. A., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936-941.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762 - Mozaffarian, D., et al. (2018). Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ, 361, k2426.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2426 - Pereira-Kotze C, et al. (2022). Conflicts of interest are harming maternal and child health: time for scientific journals to end relationships with manufacturers of breast-milk substitutes. BMJ Glob Health. 2022 Feb;7(2):e008002.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008002. - Rengel, Z., & Graham, R. D. (1995). Wheat genotypes differ in zinc efficiency when grown in the chelate-buffered nutrient solution. I. Growth and zinc uptake. Plant and Soil, 176, 307-316.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00011795 - Sadeghirad, B., et al. (2016). Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obesity Reviews, 17(10), 945-959.

https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12445 - Schulte, E. M., et al. (2015). Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0117959.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117959 - Smith, P., et al. (2015). Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415416.017 - Srour, B., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). The BMJ, 365, l1451.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1451 - Taillie, L. S., et al. (2020). An evaluation of Chile’s law of food labeling and advertising on sugarsweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: A before-and-after study. PLOS Medicine, 17(2), e1003015.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003015 - van der Wiel, B.Z., Neuberger, S., Darr, D. et al. (2023). Challenges and opportunities for nutrient circularity: an innovation platform approach. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-023-10285-x - Wakefield, S., et al. (2007). Growing urban health: Community gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promotion International, 22(2), 92-101.

https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dam001 - Welch, R. M., & Graham, R. D. (2004). Breeding for micronutrients in staple food crops from a human nutrition perspective. Journal of Experimental Botany, 55(396), 353-364.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh064 - White, P. J., & Broadley, M. R. (2005). Historical variation in the mineral composition of edible horticultural products. Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology, 80(6), 660-667.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2005.11511995 - Ziauddeen, H., & Fletcher, P. C. (2013). Is food addiction a valid and useful concept? Obesity Reviews, 14(1), 19-28.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01046.x

#Sustainability #PublicHealth #FoodSecurity #UltraprocessedFoods #UPF #Agriculture #SoilDeterioration #HealthyLiving #CorporateResponsibility #SCR